This post is part of the British Invaders Blogathon hosted by Terry Towles Canote at A Shroud of Thoughts. Click HERE for a list of all the entries!

When I was a kid, my mother rarely took me to see children’s movies. Partly because at the time (the late 1960s) there weren’t that many children’s movies made, partly because, well, she just didn’t like sitting through children’s movies.

So I was taken to see grown-up movies from a very young age. My mother has always been interested in history, and loved the royal costume dramas coming out of Great Britain at the time. She imparted this love to me.

Post-war Britain saw a decline of the historical drama, possibly because of the epic Cinemascope films, made to compete with the growing popularity of television, coming out of America. Also, filmmakers seemed more interested in contemporary subjects for both drama and comedy as Great Britain made the long recovery from the war years.

The early 1960s began a sea-change, as period dramas once again became popular in British film. The wild success of Tom Jones in 1963 likely encouraged the trend. Several periods were touched upon, but what interested me the most were the royal dramas.

There were four major films of this ilk during this period: Becket, A Man for All Seasons, The Lion in Winter and Anne of the Thousand Days. (There was also Alfred the Great, but I couldn’t find a way to see it in preparation for writing this blog post.)

All four films were based on plays. Anne of the Thousand Days, written by Maxwell Anderson, is about Henry VIII and his obsessive pursuit of Anne Boleyn. It ran on Broadway a full twenty years previously. In spite of its success, it was not adapted to the screen earlier, possibly because some of the subject matter was problematic in a Hollywood that still adhered to the Hayes Production code.

A Man for All Seasons is based in the same time period and chronicles how Henry’s Lord Chancellor Thomas More refused to endorse Henry VIII’s divorce or swear to the Act of Succession to ensure Anne Boleyn’s child Elizabeth would be first in line for the throne. The play was written by Robert Bolt and premiered in London, moving to Broadway later.

Becket, about King Henry II and his contentious relationship with Thomas Becket, who he had appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, was originally written in French by Jean Anouihl and ran both on Broadway and in London.

The Lion in Winter is also about Henry II, as a much older man who is literally at war with his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine and their children over who will succeed him. The play was written by James Goldman and was first produced on Broadway.

The four films share a similar theme: how being the dear friend or close relation of a king could be as dangerous as being his sworn enemy. In all four films, a king respectively falls out with his best friend, his closest advisor, his wife and his wife and children. In all but The Lion in Winter, this leads to death.

It’s tempting to connect these films thematically with the great social changes happening during the 1960s. In some ways, I think they do. Becket and A Man for All Seasons are certainly pleas for following ones conscience and are anti-authoritarian in spirit. Anne of the Thousand Days portrays Anne Boleyn as a remarkably complex woman, who rebels against the idea of becoming a king’s plaything. It also ends on the irony of Henry’s obsession with gaining a son when he has already fathered a child who would become one of the greatest monarchs in history. The Lion in Winter also presents complex and powerful women (both Eleanor and Henry’s supposedly pliant mistress, Alais, who turns out to be more ruthless than at first appearance).

I have to admit that upon rewatching the films for this post, I discovered that Becket (directed by Peter Glenville) is my least favorite of the bunch. It’s a great film, but something about it distanced me from it, possibly because it adheres the most to the “stagey” feel of the original play.

Henry II (Peter O’Toole, who also plays the same role in The Lion in Winter) and Becket (Richard Burton) are almost like a pair of frat boys in the beginning of the film, spending most of their time pursuing women, both willing and unwilling.

Becket is portrayed as a cold man with women. It’s only when the king appoints him as the Archbishop of Canterbury that he finds his true place in life. To Henry’s horror, instead of a compliant ally in the church, he find his erstwhile friend is now his stubborn opposition. For some reason, the movie fictionalizes the major bone of contention between them (Becket excommunicates a lord who is one of Henry’s most loyal allies; in real life, it was over restrictions Henry wanted to make on the church). The other major departure from historical fact is they make Becket a Saxon, when both his parents were of Norman descent. Perhaps this was done to add to the “outsider” quality of Becket, which both draws and repels Henry in the movie.

The movie is done as a flashback, with Henry remembering their history just as he is about to pay penance for his (supposedly) unwitting part in Becket’s assassination. This is historically accurate. In death, Becket triumphs over Henry. He was made a saint very soon after his death and even became a bit of a cult figure in Europe.

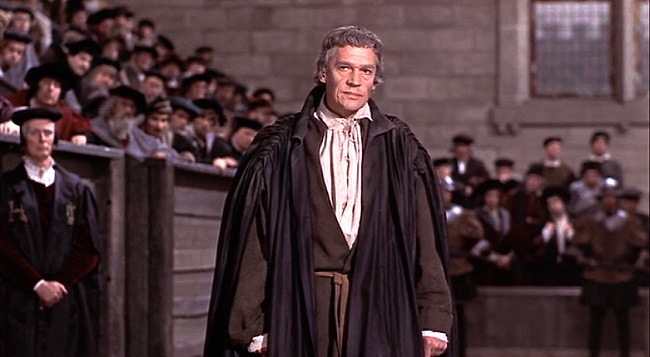

A Man for All Seasons (directed by Fred Zinnemann) is a great companion piece for Anne of the Thousand Days, obviously, but even more for Becket, as it too explores a friendship between a king and adviser that goes awry because of deeply held religious beliefs and a king’s belief in his own supremacy in all matters.

While I personally adore Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton, I have to say they are a bit on the hammy side (Burton does tone that down a bit as Becket). Paul Scofield, who portrays Thomas More, is a far more subtle actor and his performance makes the film. I object a bit to the way Thomas More’s character is whitewashed (it’s mostly agreed by historians that he was in favor of putting to death others who followed their conscience when their beliefs conflicted with his; in fact, six heretics were burned to death under his chancellorship) but I understand what Bolt was going for thematically.

In real life, More probably would have done much better to stay out of politics. He is portrayed here as the lone incorruptible man in a corrupt world. The world is so corrupt, it’s almost easy to destroy him just with innuendo. Even his own family objects to his insistence that he follow his conscience.

My favorite scene in the movie by far is between More and his wife Alice (Wendy Hiller) during their last visit in prison. As in real life, his wife is illiterate and the two seem a totally mismatched couple. When he pleads with Alice to try to understand why he’s doing what he’s doing, something even his highly educated daughter Margaret can’t comprehend, she finds a way. In a story where marriage is usually a matter of politics and/or practicality, it’s a deeply moving moment.

Anne of the Thousand Days (directed by Charles Jarrott) has a special place in my heart, because I was taken to see it on my ninth birthday and it kicked off a life-long fascination with the Tudor period of history. Now having read much about Boleyn (played here by Genevieve Bujold), both fiction and non-fiction, it’s impossible to say exactly what kind of person she truly was. The saying goes that history is written by the winners, and this is especially the case when talking about women. In this movie, she’s portrayed as a woman madly in love with Harry Percy, the heir to the Duke of Northumberland, who is furious when her marriage plans are stopped by the king. It’s more likely that Anne, whose father married “up” into one of the country’s most noble families, pursued Percy for ambition’s sake. Cardinal Woolsey (Anthony Quayle) did break up the betrothal, but not at the behest of the king (played here by Richard Burton).

She’s alternately portrayed in fiction as someone used by her family, to someone with unbridled ambition, to a religious fanatic who wanted to use her position as Henry’s wife to kick the church out of England.

In the movie, her religious beliefs are not touched upon at all, even though she was supportive of evangelicals and reformation of the church. However, she is portrayed as relishing and using the power Henry bestows upon her, which appears to be historically accurate. The film goes so far as to claim she insisted on More’s execution (that’s quite unbelievable, as Henry hardly did what other people told him to do). But it is likely that he blamed Anne for More’s death, and that may have been one reason he turned against her.

Bujold never became the star this movie promised she might become (partly because she broke her contract with Universal Studios) but she is by far my favorite Anne in popular culture, and not just because this was my first encounter with her in fiction. She plays all the nuances of the character beautifully, from heart-broken girl to cynical courtier to imperious queen to disappointed, angry wife to doomed mother. In this case, Richard Burton’s hamminess serves him well as the larger-than-life Henry.

Now comes time to talk about my favorite dysfunctional family drama of all time, The Lion in Winter (directed by Anthony Harvey). Set at a “Christmas court” in 1183 at Chinon, Anjou, it chronicles the inner-family dispute over who would succeed Henry II (O’Toole). His wife Eleanor of Aquitaine (Katharine Hepburn) has been released from custody after participating in a rebellion against her husband. Their sons Richard (Anthony Hopkins) Geoffrey (John Castle) and John (Nigel Terry), as well as Alais (Jane Merrow), Richard’s betrothed but also Henry’s mistress, await her arrival.

What follows is a series of moves, counter-moves, alliances and betrayals as the deeply estranged family tries to get Henry to name his successor. The fact that his wife and three of his children (including his late son, also named Henry) revolted against him makes him favor his youngest, if dim-witted, son John. (One reason they probably dared to revolt was the murder of Becket, which diminished Henry’s standing politically throughout Europe.) Eleanor favors her eldest remaining son, Richard. Geoffrey stands in the middle as the forgotten one.

This movie is like watching dueling giants, both when it comes to the characters and the actors portraying them. In my opinion, O’Toole’s performance here is superior to the one in Becket. Hepburn is magnificent as Eleanor, bringing the concept of a love/hate relationship to a whole new level. The younger actors do an admirable job of keeping up (no surprise, I mean, Anthony Hopkins, who was reportedly terrified of having to act with Hepburn).

By the 1970s, the royal costume drama in movies had mostly fallen out of favor, though television quickly took up the subject and produced many fine series, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Elizabeth R. In more recent years there have been the television remake of The Lion in Winter and series such as The Tudors and The White Queen. I still miss their heyday in the movie theaters, now that they’ve gone the way of the old-fashioned movie palaces. Perhaps they will make a comeback yet again.

I liked A Man for All Seasons when I first saw it, but was later rather appalled by the whitewashing of More, as you point out. Scofield does indeed ground the film, and it can be inspiring if you don’t look too closely at its historical accuracy. I can’t believe I’ve still never seen A Lion in Winter. This review reminds me why I need to! Thanks.

There is so much about More that was interesting–he was a very complex individual, and far from the perfect martyr portrayed in the film. I was not a huge fan of the series The Tudors, but they did portray some of those flaws, and I give them a lot of credit for that.

You’ve never seen The Lion in Winter? You are in for a treat!

Thanks so much for writing this! I’ve enjoyed it immensely and am a big fan of Anne of A Thousand Days (and Genevieve Bujold) also.

Thank you! So happy to meet another Anne/Genevieve fan. 🙂

I have to admit that I have the same problem with Man of All Seasons. I don’t think More is handled as well as he should have been. The film is enjoyable for me as long as I don’t think too much about the actual history! Of the films The Lion in Winter is my favourite. It does depart from history at time as well, but it enjoyable watching the power struggle among the five leads. And what a cast! I’ve often pondered if the British costume dramas weren’t a reaction to the kitchen sink dramas of the earlier Sixties myself. That is, fimmakers and audiences of tired of films shot in black and white and dealing with the working class. The historical dramas shot in colour would be about as far away from that as one could get! Anyway, thank you so much for contributing to the blogathon!

I think you’re probably quite right that the costume dramas were a reaction against the “kitchen sink” dramas. Everything goes in cycles. Interesting to see that historical dramas are making a comeback, on TV, if not the movies now. I’d love to see a big-screen historical drama again. Who knows? There was a time when no one thought superhero movies could be popular!

A Man for All Seasons is enjoyable on many levels. I don’t expect historical novels or movies to get everything right (even Hilary Mantel, who is a stickler for historical fact, deviates from fact or has to fill in blanks in her novels). It works for me as long as they get the spirit of the characters right. More was more flawed than depicted, but I do like how they portrayed him as a lawyer looking for “lawyerly” ways to get out of his predicament.

Thank YOU for hosting the blogathon–so glad I had an excuse to watch these movies again!

Now there is nothing I like more than a historical epic (perhaps it’s something to do with the costumes!). I hadn’t really considered that there had been a renaissance during the 60s, but it makes perfect sense. Of the four you mention, I’ve only seen A Man for All Seasons and The Lion in Winter; I think you have to watch them with the understanding that there WILL always be inaccuracies in film, but they’re not the lesser for it, and are in fact a reflection of the movie’s period and how our perception (and appreciation) of history is constantly in flux.

I agree–historical fiction (and futuristic fiction, too) are really about what’s happening at the time they were written. I think that’s why certain periods of history go in and out of fashion–because they reflect something happening at that moment. Right now many people seem interested in the 1920s–a few years ago, not so much.

It’s very interesting to compare the different ways Anne Boleyn is portrayed in popular culture at various time periods. And, as I mentioned, More is portrayed very differently in The Tudors (and Mantel’s Wolf Hall). Time can make a big difference in how we view historical figures.